Interview from Óxido Lento Número 4 Noviembre 2034, by Sasha Vlad

MUCH MORE THAN A FRISSON SURRéALISTE…

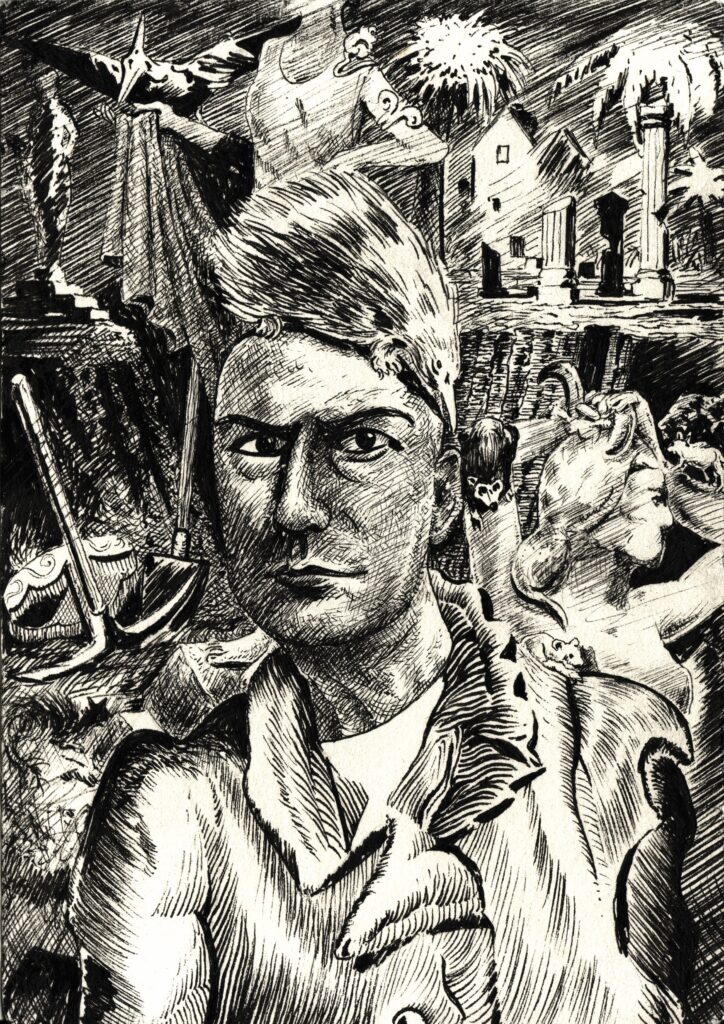

…It is cold in here! Upon entering Niklas Nenzén’s visual world, I was instantly greeted by forbidding ashen skies, foreshadowing, or possibly showing the aftermath, of devastating storms. However, at the same time, I found myself completely under the spell of an inviting, albeit strange, inner landscape. Similar to other surrealists who unwittingly reveal through specific depictions their places of origin—be they sun-drenched Catalonian beaches (Dali—alas!), impenetrable German forests (Ernst), or shifting Brittany mists (Tanguy)—there is an unmistakable Scandinavian imagery that geographically situates the world of Niklas Nenzén. This septentrional feeling is enhanced by a specific flora and fauna, and by the presence of skiers and skaters (namely, hockey players), who together with other actors populate this world, appearing in unexpected juxtapositions, absurd situations, or involved in dream narratives.

Evidently, my initial impressions expressed in the above preamble do not exhaust the poetic beauty and complexity of Nenzén’s work. Therefore, it is incumbent on me to ask the artist himself to shed light on some secrets of his world.

S.V.: Hello, Niklas. Let me begin by asking you the following: are my first impressions regarding your work somewhat truthful?

N.N.: Yes, your impressions probably pinpoint some vital aspects of what my work conveys. The coldness has been noted before. When I exhibited in New York 2017 a title for the exhibition was suggested to me, that seemed evocative enough to use: The Air is Frozen at the Luxury Hotel. It makes me think of the coldness of ghostly apparitions, of possible lost civilizations under the ice caps, of circulating space debris and of Prince Hat’s subterranean lair in the Scandinavian forest. Also, I was a hockey player in my youth, and to me there is a connection between hockey skating and drawing; at some level, my nervous system knows of no difference of pen and skates, sheets of paper and ice and, cross hatching and transition turns. I’m foremost a draughtsman. I like the dialectics of drawing. I like that in a single isolated line you can trace how deliberation and improvisation, convulsion and perfection, collapse into each other.

S.V.: I am glad to see that we ”broke the ice” this way! The cold, the fairytale world of Prince Hat Under the Ground and the connection between skating and drawing are all extremely relevant. And, since we got a glimpse into your biography, when and how did you discover surrealism?

N.N.: My first encounter with surrealism was José Pierre’s A Dictionary of Surrealism, which I bought as a teenager. It is still my favourite book about surrealism, mainly due to the excellent selection of images. I was profoundly influenced by it, especially by Dali and Bellmer (both also embarrassed me). It made me produce a lot of drawings, some of which I later photocopied and sent to the Surrealist group of Stockholm, probably in 1996. I was invited to attend the group´s meetings and befriended some creative individuals who employed autonomous, non-routinized approaches to surrealism that inspired me further, such as Bruno Jacobs, Mattias Forshage, and John Andersson, and later Emma Lundenmark.

S.V.: Beside Dali and Bellmer, who else influenced you? Was there also a possible connection with the Imaginisterna (”Imaginists”), if not in style, maybe in spirit?

N.N.: Any and all! The ones that have stuck with me are Chirico (all periods), Varo, Trouille, Magritte (drawings, notebooks). No, the only Swedish surrealism-affiliated artist from the old guard that affected me greatly was Öyvind Fahlström. Especially his painted collages and irreverent ideas of abstract storytelling. I have always liked images that suggest stories. Hence, I was more influenced by Golden Age comics, turn-of-the-century fairy-tale illustrations, pictorial dictionaries, and album covers for metal and prog rock, than by art.

S.V.: I cannot resist the temptation to comment a little on what you said. Öyvind Fahlström is fascinating, indeed. I also like the fact that you specified ”all periods” about de Chirico, which is in total opposition with the repudiation of his later period by the early surrealists. Fairy-tale illustrations may refer to John Bauer, and rock album covers could be mostly about Hipgnosis, I assume?

N.N.: Yes, for me Chirico’s later works are stunningly pseudo-amateur, ironic, puzzling, challenging, easy-going, and self-destructive. Some of his paintings even have strange cartoonish qualities, as if Hergé had decided to paint metaphysical piazzas. Such contradictions make art fun and interesting, I think, especially with a painter like Chirico who always manifests his essence, in good and bad, and does so with stylistic variation. Trouille and Fahlström also have this amateurish and irreverent ”pop” wildness about them. Yes, when it comes to illustrators, Bauer is of course a master, as are Dorothy Lathrop, Kay Nielsen, Virginia Frances Sterrett and countless others. There is so much going on in the art nouveau styles of fairy tale illustration that I sometimes think surrealism is just one aspect of it (the marvellous in avant garde art?). In comics, I like intensely original and art-brutish artists like Fletcher Hanks and Augusto Pedrazza, but also more anonymous industrial products of the past. Of course, when I was growing up, a lot of creativity and imagination was invested in turning records and comic books into beautiful and terrifying cult objects. I was heavily influenced by imaginative album covers, which were sometimes made by daring amateur artists or fanatical musicians, and by how painters interpreted music and vice versa. The cult of listening and looking at a sleeve you´re holding in your hand! I always listen to music when I draw or paint.

S.V.: Since you earlier mentioned comics, what specifically attracted you to this means of expression? Also, in what way are comics suitable when narrating dreams?

N.N.: I’ve never gotten rid of the impression I had as a child, that comics are the most oneiric form of art (i have always dreamed comics and about comics). The plasticity and exaggeration that we see in comics and in cartoons seem to me to be present in dream states too. The same goes for caricature: excess of character gives an unnatural impression, as Hegel comments. For me, comics are a double-edged sword when it comes to narrating dreams. On the one hand, it may seem an eminently suitable medium for rendering the temporal aspect of how we experience things in dreams. On the other hand, I have often noticed that faithful reproduction may be technically and artistically very impossible to achieve. Failure of representation also tends to reveal the deceitfulness of it: because of one’s technical or artistic shortcomings, one finds one has unintentionally misrepresented the dream so that it became something other than one believed it to be. Which certainly can also make one realize that the dream had no form before drawing it (or writing it down). Perhaps the dream is not fully dreamed until it has been told to someone who reacts to it?

S.V.: While exploring dreams and comics, you found a worthy collaborator in John Andersson. What are your thoughts on Diabolik, your common project, and on collaborations in general?

N.N.: I enjoy collaborations in general, both for their synergetic possibilities and for communitarian reasons. I met John Andersson in 1996 through the surrealist group of Stockholm and we became involved in many projects over the years, such as exhibiting together, and making the surrealist comic magazine Diabolik. Since we both regulary dreamed (about) comics, our intention in creating the magazine was to produce something that had the same effect as encountering a dream object, or a cargo cult-like object from an unknown world, ”dripping with ghost mist” as John put it. Socially, it was supposed to convey the fluid quality of ”magma”, that is: of welling up from ”below” the milieu of underground comics (with its relatively fixed styles, themes and conventions). We also wrote a programmatic article together, ”The Place of the Soul”, where we expressed mutual views on fantasy, atmospheres, and enigmas in image-making. Here is an excerpt:

”After all, atmospheres are a prerequisite for life both in terms of planets and art, or just where something emotionally interesting happens, such as on occasions for falling in love or chance encounters. An atmosphere is a psychic space, a secret about yourself, which, like a large unopened envelope, lingers in the air, waiting to be revealed. What causes psychic space to gravitate toward actual space? That the riddle is still unanswered.”

Like Magritte, we liked to think of images in terms of the ”magic” and ”mystery” of beauty. An image in that sense can be viewed as an ongoing series of contrasts that never gets resolved into a final harmony. The magic is the invocation of attraction, the mystery is that the tension remains. Simplistically speaking, it remains a pleasure looking at the image…

S.V.: The pleasure of looking at the image, indeed! On this note, thank you for shedding light on some key aspects of your creation. In closing, would you like to add anything as a response to a question that I failed to ask?

N.N.: Thank you for the perceptive reading of my images and for a stimulating conversation. The wind of Septentrio shall wrap its cloak around anything unsaid…

April-May 2024